Thoughts and challenges for clinicians treating persons with head and face problems

Introduction

As we all face new and unforeseeable challenges due to the current COVID-19 or “Corona-Virus” pandemic, more and more clinical thoughts and implementations turn up. Next to possibilities and applications of new and modern technologies in rehabilitation, like telemedicine, telerehabilitation or the use of virtual reality, the patients´ and the therapists´ safety have to be considered, especially when a stepwise return to face-to-face therapy occurs (Eccleston et al., 2020; Haines & Berney, 2020).

Another point that has to be considered is the way we cover our faces by (surgical) masks, which cover our mouth and nose so only the eyes and forehead are free. Whereas the daily and common use of these masks is very established in Asian countries (Yang, 2020) the everyday viewing is still very unusual in middle-European countries, the US, Canada, and many other countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) is constantly adapting its recommendation of when and how to use different kinds of masks during the ongoing pandemic (WHO, 2020). Different guidelines in several countries advise the use of face mask protection for the patients and the therapists during face-to-face work with but this normally applies to the acute care setting and patients (Physio Austria, 2020).

We may ask ourselves what’s happening with our nonverbal communication skills considering that most of our emotions and feelings are expressed by the face. In this blog, we discuss some thoughts and ideas about how to deal with this situation in the daily clinic in the future.

Our face as a communication tool

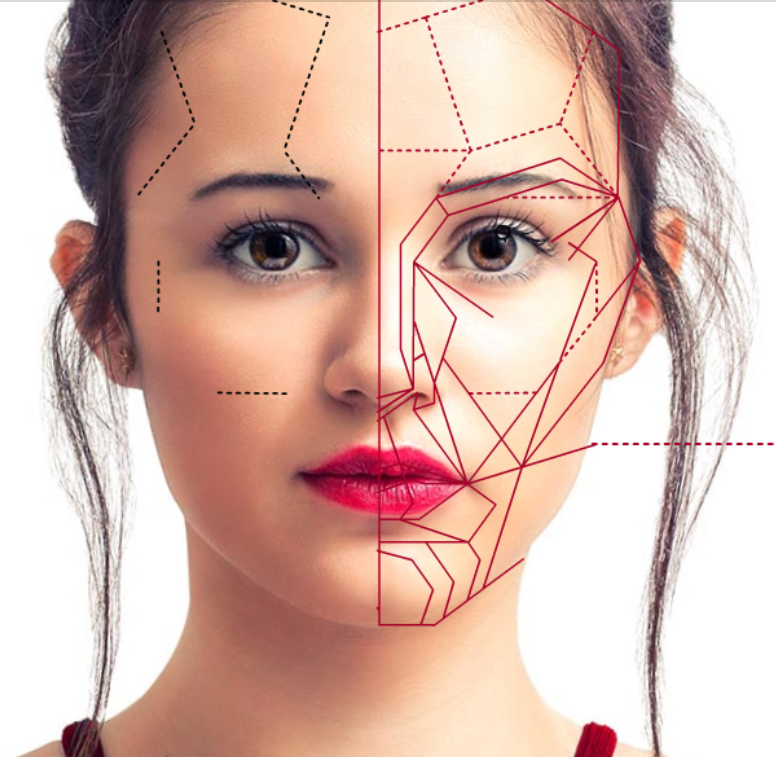

Our face has the unique ability to communicate in a nonverbal manner (von Piekartz & Mohr, 2014). Nonverbal communication is dependent on facial emotional expression, which often works as an early warning system and shows us how the person might feel at the moment (von Korn et al., 2014). Empirical evidence confirms that our own facial expressions´ feedback modulates our emotional experiences (Price et al., 2015). For instance, smiling of a person (stimulus) initiates directly the smiling facial motor activity in another person’s “facial mimicry.” This may facilitate an emotional response (happiness) and other physical reactions like autonomic arousal (sweating, heartbeat changes) and bodily motor responses (smile) which is called “facial mimicry.” Besides storing this somato-sensory-motor experience, the brain scrutinizes it against millions of other facial mimicry experiences it has experienced previously, which leads to subtle individual non-verbal communication and empathy (Wood et al., 2016).

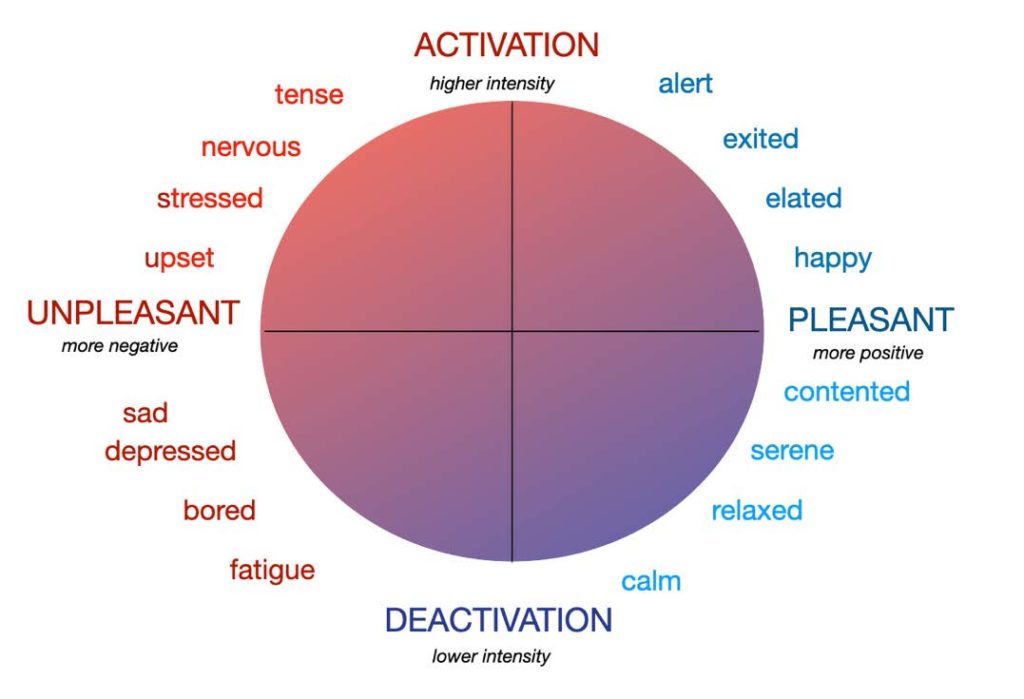

Another idea is the emotion-circum-flex-model, where there is a mixture of different “fused” facial expressed emotions with different durations and intensities, which may be expressed in positive/negative feelings or moods with variability of intensity (Russel et al., 2003). In this case, more than 6,000-8,000 different fused facial expressions may act to clarify what we mean and what we want and feel to another person in different contexts and tasks. Various studies have shown, that our first reflex is scanning of another person’s face, mainly the eyes and mouth. From an evolutionary point of view, we assess whether there is a threatening situation (Ross et al., 2007). Especially the lower part of our face (the region of the mouth) plays a role in the recognition of disgust, anger, and happiness (Wegrzyn et al., 2017).

Partial covering our face. What does it do to us?

Partial covering (occlusion) of faces (particularly the eyes and mouth) influences the accuracy and speed of the recognition of emotions, which may occur in children and adults (Roberson et al., 2012). In general, mouth occlusion causes a greater decrease in facial expression recognition than the occlusion of the eyes. Mouth occlusion affects especially anger, fear, happiness, and sadness, while eye occlusion affects mainly feelings of disgust (Kotsia et al., 2007). This data is the result of clinical research and mostly occurred during a short time of face occlusion. There is no long-term face occlusion data available, but persons with general chronic pain, facial pain, Parkinson’s disease, facial paresis, depression or following a stroke are less accurate and slower in emotion recognition and expression. This may lead to emotion blindness referred to as alexithymia (Taylor & Bagby, 2004).

Can blending your face be an advantage?

Partially covering our face in a reflex, which involves mostly the lower part, can also help us covering our real emotion, especially if we are not allowed to express our emotions, because of norms and values in that particular situation. For example, somebody tells you a joke during a classic concert and you have to laugh. Or when you smell disgusting odors coming from food cooked specially for by a dear friend. This phenomenon is referred to as “facial blending” (Ross et al., 2007).

Partially covering our face in a reflex, which involves mostly the lower part, can also help us covering our real emotion, especially if we are not allowed to express our emotions, because of norms and values in that particular situation. For example, somebody tells you a joke during a classic concert and you have to laugh. Or when you smell disgusting odors coming from food cooked specially for by a dear friend. This phenomenon is referred to as “facial blending” (Ross et al., 2007).

At a property company in Northern China’s Handan province, everybody wears masks on Tuesday as part of their “faceless day”. This is the most relaxed day for every employee because you can’t see if somebody is smiling or angry, so you can make whatever facial expressions you want without getting a written warning.

At a property company in Northern China’s Handan province, everybody wears masks on Tuesday as part of their “faceless day”. This is the most relaxed day for every employee because you can’t see if somebody is smiling or angry, so you can make whatever facial expressions you want without getting a written warning.

Does wearing mouth-nose (surgical) masks have real consequences for us in our society?

Could long-time wearing surgical masks influence or change our facial mimicry which may lead to a kind of alexithymia – let´s say, “surgical mask alexithymia” based on the “Russell Model” (2003)? Will our emotions be flatter and less intense and show fewer changes in the balance of negativity? Are we becoming more human individuals when our unique variability and intensity of emotions decrease in a world where we are “locked down“ by a pandemic situation with no time limit? If you believe in conspiracy theories of the “New World Order,” where (world) authorities commit us to wear masks, could this be a powerful contributing instrument to fulfill the globalist agenda faster then usual?

Does wearing a mask have consequences for workers in the cranio-oro-facial field?

Part-time face blend during a fearful pandemic society with no time limit may have a strong impact on (cranio-facial) patients and clinicians. Some questions we may ask ourselves:

- Will masks, worn by therapists and patients, disturb communication, due to a lack of facial reflexes and mood estimation?

- Do facial expression restrictions have consequences for the quality of life of orofacial patients with, for example, TMD, bruxism, or traumatic face pain?

- Depression and catastrophizing often are comorbidities in this patient group. Does wearing masks have a greater impact on their complaints?

- How can we recognize/test if a lack of or a change in emotional responses and processing may be a risk or contributing factor to the patients’ complaints?

- If we recognize any such consequences, what are the possibilities for intervention?

Challenges for musculoskeletal research and treatment

The 1.5-meter (6 feet) social distancing and the facial blends by the surgical masks force us to adapt our thoughts about research and the assessment and treatment strategies. For example:

- Is (surgical) “mask alexithymia” more often seen by craniofacial patients with a mask compared to without?

- Is specialized manual treatment and pain neuroscience education (PNE) sufficient to reach the proposed goals?

- Do we have to incorporate the consequences of facial blending by masks during PNE?

- Do we have to test the status quo of emotion recognition/expression and the change of cognitive style patients use?

- When emotion recognition and expression are blurred, can we train these with facial motor function training, motor imagery, and emotion training?

Perhaps, there are other questions to consider. Please don’t hesitate to react or write us an email (info@crafta.de)!

Testing and Training

At least we can start testing and try to integrate emotion (face) training:

At least we can start testing and try to integrate emotion (face) training:

- In psychological studies, the Reading-the-Mind-in the-Eyes Test is often used which shows good accuracy of recognizing the emotional and behavioral state in a person’s eyes (Sato et al., 2016).

- The Facially Expressed Emotion Labeling (FEEL) Test, which is a computer-based test, measures one’s ability to recognize facially expressed basic emotions (Braun et al., 2005).

- Our Face Training website is a software program for PC and mobile devices as an APP, which gives clinicians the opportunity to test and train the emotion recognition/expression. It even has a mirror function!

- The Face training App CRAFTA® is a simple APP to test and to train laterality and basic emotions.

Conclusions

- Clinicians should be aware that facial deprivation during the COVID-19 pandemic in combination with imposed social restriction for an indefinitely time may have a profound impact on the quality of life and pain, especially in craniofacial sufferers.

- Clinicians should be aware of possible new clinical patterns

- Clinicians should apply standardized tests to evaluate the emotion responses and train these if necessary.

Do you have any additional ideas or thoughts on this topic? Please share your thoughts on CRAFTA® Facebook or email us at info@crafta.

Bernhard Taxer, MSc PT, PhD Cand., CRAFTA®, Austria

Harry von Piekartz, PhD, MSc PT, CRAFTA®, Netherlands

References

Braun, M., Traue, H. C., Frisch, S., Deighton, R. M., & Kessler, H. (2005). Emotion recognition in stroke patients with left and right hemispheric lesion: Results with a new instrument—the FEEL Test. Brain and Cognition, 58(2), 193-201

Eccleston, C., Blyth, F. M., Dear, B. F., Fisher, E. A., Keefe, F. J., Lynch, M. E., Palermo, T. M., Reid, M. C., & Williams, A. C. de C. (2020). Managing patients with chronic pain during the Covid-19 outbreak: Considerations for the rapid introduction of remotely supported (e-health) pain management services. PAIN, Articles in Press. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001885

Haines, K., & Berney, S. (2020). Physiotherapists during COVID-19: Usual business, in unusual times. Journal of Physiotherapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2020.03.012

Kotsia, I., Buciu, I., & Pitas, I. (2008). An analysis of facial expression recognition under partial facial image occlusion. Image and Vision Computing, 26(7), 1052-1067. Physio Austria. (2020). Coronavirus: LAUFEND neue Informationen für PhysiotherapeutInnen | physioaustria.at. https://www.physioaustria.at/news/coronavirus-laufend-neue-informationen-fuer-physiotherapeutinnen

Price, T.F. and Harmon-Jones, E. (2015) Embodied emotion: the influence of manipulated facial and bodily states on emotive responses. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 6, 461–473

Roberson, D., Kikutani, M., Döge, P., Whitaker, L., & Majid, A. (2012). Shades of emotion: What the addition of sunglasses or masks to faces reveals about the development of facial expression processing. Cognition, 125(2), 195-206

Ross ED, Prodan CI, Monnot M. (2007): Human Facial Expressions are organized functionally across the upper-lower facial axis. Neuroscientist, Vol. 13(5): 433-446

Russell, J. A. (2003). Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychological Review, 110, 145–172

Sato, W., Kochiyama, T., Uono, S., Sawada, R., Kubota, Y., Yoshimura, S., & Toichi, M. (2016). Structural Neural Substrates of Reading the Mind in the Eyes. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00151

Taylor, G. J., & Bagby, R. M. (2004). New trends in alexithymia research. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 73(2), 68-77

von Korn, K., Richter, M., & von Piekartz, H. (2014). Einschränkungen in der Erkennung von Basisemotionen bei

Patienten mit chronischem Kreuzschmerz. Der Schmerz, 28(4), 391–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00482-014-1395-5

von Piekartz, H., & Mohr, G. (2014). Reduction of head and face pain by challenging lateralization and basic emotions: A proposal for future assessment and rehabilitation strategies. The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 22(1), 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1179/2042618613Y.0000000063

Wegrzyn, M., Vogt, M., Kireclioglu, B., Schneider, J., & Kissler, J. (2017). Mapping the emotional face. How individual face parts contribute to successful emotion recognition. PloS one, 12(5)

WHO (2020). When and how to use masks. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/when-and-how-to-use-masks

Wood, A., Rychlowska, M., Korb, S., & Niedenthal, P. (2016). Fashioning the face: sensorimotor simulation contributes to facial expression recognition. Trends in cognitive sciences, 20(3), 227-240

Yang, J. (2020). A quick history of why Asians wear surgical masks in public. Quartz. https://qz.com/299003/aquick-history-of-why-asians-wear-surgical-masks-in-public/