In the Netherlands, the accreditation commission of the Dutch Society of Physical Therapy (KNGF) criticized the manipulative assessment and treatment approach of the Craniofacial Therapy Academy (CRAFTA) education and rejected more than 50% of the possible accreditation points which were supposed to be credited to post-graduate physical therapists. No accreditation points were awarded to manual therapists, which in the Netherlands, is a different professional qualification. The main reason for the decision of the committee was that “the techniques which are used are osteopathic techniques and are not evidence-based. The techniques are NOT based on Western rationales.”

In this blog, Dr. Harry von Piekartz explains what cranial manual therapy is all about. To learn more, considering attending the CRAFTA courses, hosted by Myopain Seminars.

What is cranial manual therapy?

In the CRAFTA education, cranial manual therapy is defined as:

the assessment and treatment of the cranium (head) and the face with passive movements (movements executed by the therapist).

During the examination, three parameters are examined: resistance, rebounce and sensory response:

- Resistance: is the start and the quality of the pressure, which is analyzed during the increased pressure of the passive movements (Maitland et al 2013)

- Rebound: a reaction of the cranial bone tissue by decreasing tension executed by an external force like a passive movement. This reaction is based on the cranial architecture and the transduction of forces between the bone structures commonly referred to as the stress transducer system (Oudhof 2001, Proffit 2013 ).

- Sensory response: the personal experience by the patient during the performing of cranial passive movement, e.g. pain, dizziness, tinnitus, heavy body feeling and others.

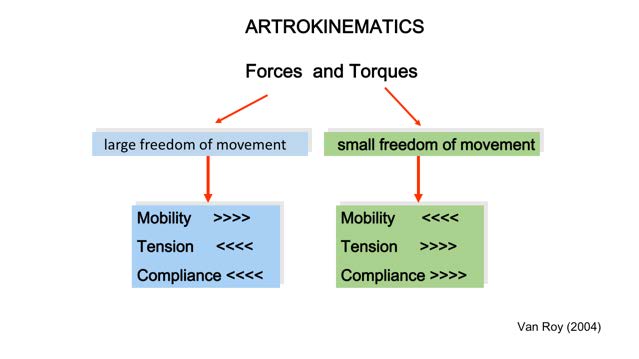

Arthrokinematics of a (human) functional movement unit comparing units with a large freedom of movement (i.e., shoulder complex) and small freedom am movement ( ex. Symphysis, Cranium)

Initially, the three parameters will be examined through six standard tests. Next, specific regional tests are performed based on the results of the six standardized tests. Abnormal findings like increased resistance, reduced rebound, or the reproduction of the patient’s symptoms (sensory responses) may provide information or possible clues, or supporting clinical patterns. Clinical patterns might stem from, for example, post-traumatic headache, unilateral subjective tinnitus, facial trauma, chronic (pseudo) sinusitis, or pediatric ear pain.

The parameters are based on the evidence from cranial growth models and research from the scientific fields of orthodontics, plastic surgery, and neurosurgery (Smith and Josell 1986, Proffit 2013) and the latest pathobiological knowledge from pain science and the innervation of cranial tissue (Schueler et al 2013).

What is the difference between cranial manual therapy (CM) and craniosacral therapy (CS)?

There is strong clinical evidence that cranial passive movements may alter pain complaints and function in human beings. For an excellent overview of the different models, the reader is referred to Leon Chaitow’s book “Cranial Manipulation. Theory and Practice” (Chaitow 2005). Most of the models are driven by the cranial-sacral rhythm. This is a cyclic movement of all body tissue related to the movement of the spinal fluid, also known as the “primary respiratory mechanism.”

- CM is based on growth studies coming from the fields of orthodontics, plastic surgery, and neurosurgery. This is in contrast to the ideas of CS and the primary respiratory mechanism.

- CS is based on biomechanical/anatomical models. CM focuses on functional/biological/ pragmatic models.

- The treatment goals are different – In the CM assessment and management techniques, the clinician looks for specific clinical signs, such as resistance, rebound, and sensory response. CS is focused on changes in structures and systems (suture, ventricle, psycho-emotional systems). – CM always combines craniofacial functions, such as eye movements, respiratory and tongue exercises/ training. CS is a more passive approach that aims to trigger the “self-healing’ mechanism of the body. This is a crucial difference with cranial manual therapy.

- CM does not aim to mobilize sutures, as it is known from many studies that several kilograms are needed to achieve minimal sutural movement (Downey et al 2005)

- CM does not aim to alter ventricles and does not base the effects on the cranial sacral rhythm due to the lack of evidence (Sommerfield et al 2004 )

- CM does not aim to treat patients with a passively and a “wait and see” approach following the treatment

- CM does include a systematic analysis of the abnormal tension in the cranial bones relative to the patient’s complaints, which are expressed in three parameters (resistance, rebound, and sensory response). It is based on pain mechanisms and the classification of pain ideas.

- CM does support the biological functions of the cranial tissue during growth and to reduce nociception in the craniofacial area.

- Further, CM aims to restore function (normal stress-transduction) and to stimulate craniofacial organ function

Is there evidence for cranial manual therapy?

Stress and strain function of cranial bones may be influenced by craniofacial (dys-) functions (Gabutti and Draper 2014). Further, pericranial tissues can directly influence meningeal nociception associated with symptom-like headaches ( Schueler 2014), however, a systematic effect study is still lacking.

In a systematic review by Krützkamp et al (2014) of the outcomes of the treatment of the craniofacial tissue by passive movements, 37 studies were identified related to orthodontic splint therapy, craniosacral or manual therapy as passive interventions. All had poor methodological quality and small subject groups. Only very little evidence could be identified concerning the outcome of all therapy approaches on headaches and psychogenic problems, which suggests that the Dutch accreditation commission may be correct, that there is a lack of direct scientific evidence based on effect studies.

However, empirically gathered knowledge by therapists, patients, and external evidence from other disciplines help to better understand the function of the craniofacial region. This collective knowledge supports the cranial manual therapy model which is clearly NOT the same as craniosacral therapy.

References

- Chaitow L, Cranial Manipulation Theory and Practice, 2nd Edition, 2005, Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

- Downey PA, Barbano T, Kapur-Wadhwa R, Sciote JJ, Siegel MI, Mooney MP. Craniosacral therapy: the effects of cranial manipulation on intracranial pressure and cranial bone movement. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006 Nov;36(11):845-53.

- Gabutti, M, Draper-Rodi J Osteopathic decapitation: Why do we consider the head differently from the rest of the body? New perspectives for an evidence-informed osteopathic approach to the head International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine (2014) 17-23

- Krützkamp L, D Möller, von Piekartz H. Influence of Passive Movements to the Cranium systematic Literature review. Manuelle Therapie 2014; 18: 183–192 Maitland G, Hengeveld E, Banks K, English K. Vertebral manipulation, 6th ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2013

- Oudhof H. Skull growth in relation to mechanical stimulation. In: von Piekartz H, Bryden L. Cranialfacial Dysfunction and Pain, Assessment, Manual Therapy, and Management. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2001

- Proffit WR. Contemporary Orthodontics. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Year Book; 2013

- Schueler M, Messlinger K, Dux M, Neuhuber WL, De Col R. Extracranial projections of meningeal afferents and their impact on meningeal nociception and headache. Pain. 2013, Sep;154(9):1622-31

- Sommerfeld P, Kaider A, Klein P. Inter- and intraexaminer reliability in palpation of the “primary respiratory mechanism” within the “cranial concept”. Man Ther. 2004 Feb;9(1):22-9

- Smith R, Josell The plan of the human face: a test of three general concepts. Am J Orthod. 1984 Feb;85(2):103-8.