Physical Impairments in the Dancer Population

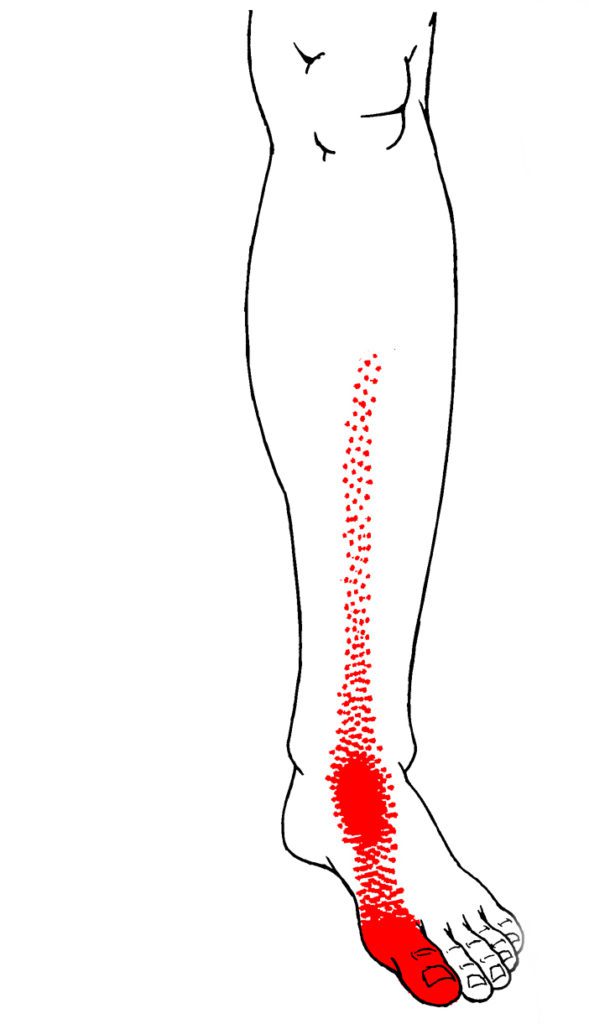

As with any athlete or performer, dancers in all genres often develop trigger points because of overuse, poor technique, overloading, or trauma. Trigger points may result in impairments, including pain, range of motion restrictions, muscle inhibition, increased muscle tone, and muscle activation patterns, and motor control changes. Referred pain patterns from trigger points may also mimic other musculoskeletal and nerve pathologies and injuries, especially in a dancer population. For example, after a dancer collides with another dancer, she may develop a large hematoma on her shin. The hematoma is painful but resolves after a normal healing period of 7-10 days. However, the dancer begins experiencing anterior ankle and great toe pain with no known trauma or injury to the area. It is possible that the shin trauma caused TrPs to develop in the anterior tibialis muscle, which refers directly to the anterior ankle and great toe. Thus, by treating the trigger points in the anterior tibialis, which may involve trigger point dry needling, the pain is resolved.

As with any athlete or performer, dancers in all genres often develop trigger points because of overuse, poor technique, overloading, or trauma. Trigger points may result in impairments, including pain, range of motion restrictions, muscle inhibition, increased muscle tone, and muscle activation patterns, and motor control changes. Referred pain patterns from trigger points may also mimic other musculoskeletal and nerve pathologies and injuries, especially in a dancer population. For example, after a dancer collides with another dancer, she may develop a large hematoma on her shin. The hematoma is painful but resolves after a normal healing period of 7-10 days. However, the dancer begins experiencing anterior ankle and great toe pain with no known trauma or injury to the area. It is possible that the shin trauma caused TrPs to develop in the anterior tibialis muscle, which refers directly to the anterior ankle and great toe. Thus, by treating the trigger points in the anterior tibialis, which may involve trigger point dry needling, the pain is resolved.

Muscle Inhibition

Inhibition of key muscles that provide support or stability may also interfere with symptoms. For example, when the gluteus medius is impaired, abnormal stresses may be placed on proximal or distal structures. Therefore, the practitioner must identify and treat trigger points in the kinetic chain, possibly quite far from the painful region. Addressing trigger points in the gluteus medius and quadratus lumborum muscles may be integral in addressing patellofemoral, ankle, foot, or toe pain.

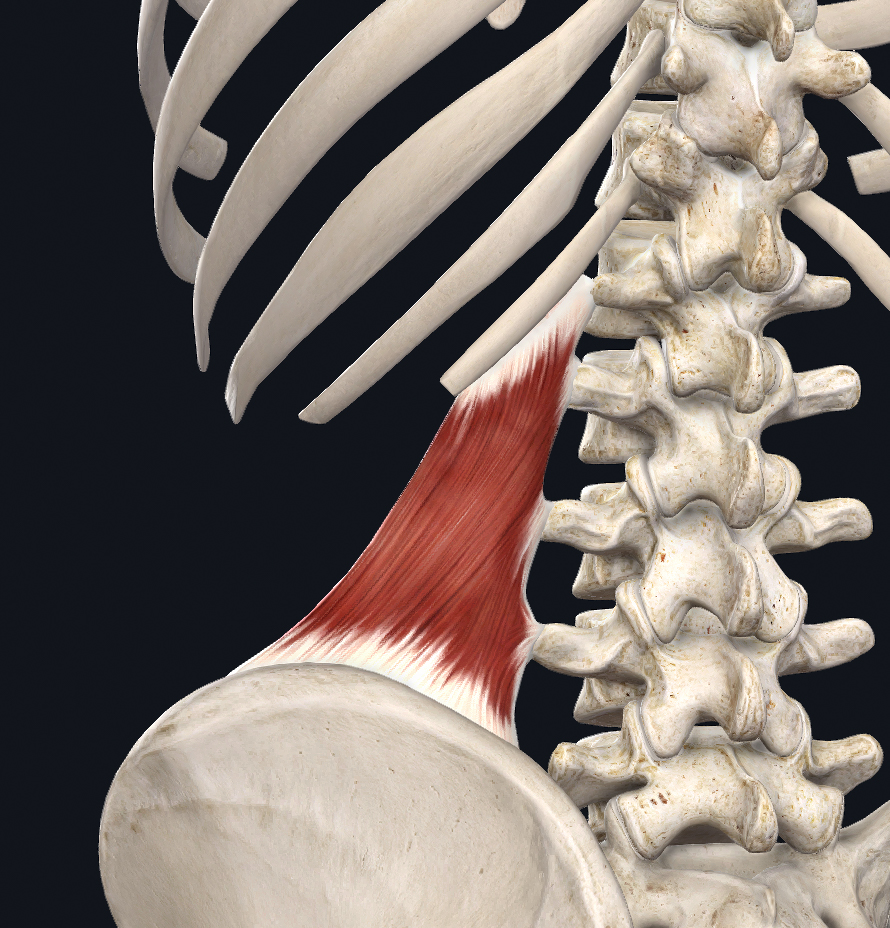

Similarly, practitioners must keep in mind some “key” muscles when evaluating a dancer with low back pain, both with and without a radicular pain pattern. The quadratus lumborum (QL) is one of these key muscles, as it can mimic herniation disc pain or a lateral shift in the lumbar spine. It may appear as a lumbar scoliotic curvature or contribute to a functional leg length discrepancy. Quadratus lumborum pain is commonly due to primary trigger points in the QL leading to inhibition and weakness in the gluteal muscles, which in turn may decrease the dancer’s ability to stabilize the hip and pelvic girdle on that side.

Similarly, practitioners must keep in mind some “key” muscles when evaluating a dancer with low back pain, both with and without a radicular pain pattern. The quadratus lumborum (QL) is one of these key muscles, as it can mimic herniation disc pain or a lateral shift in the lumbar spine. It may appear as a lumbar scoliotic curvature or contribute to a functional leg length discrepancy. Quadratus lumborum pain is commonly due to primary trigger points in the QL leading to inhibition and weakness in the gluteal muscles, which in turn may decrease the dancer’s ability to stabilize the hip and pelvic girdle on that side.

Therefore, treating the QL first may also help to address additional impairments in the patient’s presentation. Other muscles that may be important in the examination of a patient with non-specific low back pain include the abdominals, the adductors, the lumbar multifidi, and paraspinals, among others.

Trigger Points in Dancers

In a dancer presenting with more sciatic nerve or discogenic pain, TrPs should also be considered. For example, according to Travell, the gluteus minimus muscle’s referral pattern travels down the posterior and lateral aspects of the thigh, leg, and into the foot. This pattern may mimic a radiculopathy, but the patient may not present with other typical findings of an L4/5 disc herniation, such as changes in dermatomes, myotomes, reflexes, etc. Additionally, TrPs in the deep external rotators of the hip (piriformis, gemelli superior and inferior, obturator internus and externus, and quadratus femoris) may cause shortening of these muscles, limited internal rotation of the hip, and a pain pattern consistent with “piriformis syndrome.”

Because of muscle length effects, this patient may also present as positive for typical special tests for piriformis syndrome (FAIR, FADIR, etc.). Clinically, treating the deep rotators should resolve both the pain and range of motion restrictions. When dancers present with anterior hip pain, in the setting of decreased external rotation and gluteal trigger points, the release of the trigger points is often an effective first step in reducing pain and facilitating recruitment of the muscles for neuromuscular retraining and pelvic stabilization.

The Differential Diagnosis of Foot Pain in Dancers

In the dancer population, we often see patients with complaints of foot pain; stress fractures/stress reactions should always be considered as a source of symptoms, as stress injuries are more common in this group. However, TrPs should also be included in the differential diagnosis, especially if the tuning fork testing is negative before investigating more expensive imaging. For example, the soleus refers directly to the plantar surface of the calcaneus and may mimic a calcaneal stress fracture.

Additionally, if the TrPs in the soleus are causing muscle shortening, the dancer may also present with limited dorsiflexion and changes in the biomechanics for plié, jumping, and landing. Other common sites for stress responses include the anterior tibia, distal fibula, and the metatarsals. All of these may have TrPs as contributing factors to the pain presentation: tibialis anterior, fibularis muscles, extensor digitorum longus and brevis, extensor hallucis longus and brevis, and plantar and dorsal interossei, among others. Trigger point diagnosis and management is often an essential aspect of the evaluation.

Examination of Key Muscle Groups

Dancers are often diagnosed with plantar fasciitis when presenting with pain in the arch of the foot. In addition to traditional treatments, to provide dancer foot pain relief, the practitioner should consider a group of muscles that may be related to this pain presentation, especially if the dancer is frequently jumping. The gastrocnemius should be examined first, as it refers directly to the arch, and may also limit dorsiflexion range of motion. Other muscles to consider are the flexor digitorum longus, quadratus plantae (flexor accessorius), and flexor digitorum brevis. Clinically, this author tends to examine larger and more proximal muscles first, then more distal and into smaller muscles. Again, in this case, TrP DN to the gastrocnemius may resolve both pain and range of motion complaints frequently seen with a plantar fasciitis diagnosis.

Concussions and Whiplash

Concussion and whiplash injuries have become more common in dance as the difficulty of choreography demands increases. For example, a dancer may fall from a lift, be thrown into a set-piece, or be kicked by another dancer. While a typical concussion exam and neurological assessment should always be performed, TrPs should also be assessed for their potential contribution to pain, range of motion restriction, muscle weakness, and other symptoms after head trauma or a whiplash injury. The sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle is often involved in concussion and whiplash injury due to the eccentric load that occurs with a coup-contrecoup mechanism. Trigger points in the SCM may produce a variety of symptoms including, but not limited to, ipsilateral and contralateral headache, jaw pain, tinnitus and pressure in the ear, sinus pain, lacrimation, vertigo, etc. Similarly, TrPs in the longus colli and other deep cervical flexors may present as throat pain, a “lump” in the throat, or difficulty swallowing, which are all common symptoms after a whiplash injury. If the injury is chronic, insomnia and depression may impact dancers’ well-being and their ability to improve.

Somatic Symptoms from Anxiety

Dancers tend to have perfectionist tendencies and may present with higher levels of anxiety than their non-dancer counterparts. Clinically, this personality type may present in various somatic manifestations, including frequent headaches and jaw pain. Again, TrPs should be considered as contributing factors, and the following muscles should be examined: suboccipitals, posterior cervical musculature, upper trapezius, levator scapulae, medial and lateral pterygoid, temporalis, masseter, SCM, etc.

Trigger points may also present as a result of acute injury. In the case of a dancer presenting with a lateral ankle sprain due to a plantarflexed and inverted landing, the fibularis longus, brevis, and tertius muscles may also respond with trigger points due to eccentric overload sustained during the injury. These trigger points may be the cause of persistent lateral ankle pain.

Considering Trigger Point Dry Needling

Keep in mind that every dancer and injury presentation may not be appropriate for trigger point dry needling. Clinicians may choose to address trigger points with manual trigger release and by teaching the dancer to perform self-trigger point release using their hands, a ball, or a foam roller.

Mandy Blackmon, PT, DPT, OCS, CMTPT

Top Photo by David Hofmann on Unsplash